Why lung health matters

Most clinicians know that Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, or COPD, is a major problem around the world. But as with many other conditions, the true extent of the problem is not entirely understood. Here in the United States, approximately $50 billion is spent on COPD annually, between the direct costs of healthcare delivery and the indirect costs that the economy endures as a result, like lost productivity and absenteeism.1 Some 15 million or so people have been formally diagnosed with COPD, and it is fourth-leading cause of death in America. Of course, COPD is not merely an American problem; there are approximately a quarter of a billion people living with the condition around the globe, where COPD is actually the THIRD leading non-pandemic cause of death.2

COPD - The “invisible epidemic” #

And yet, this is still only part of the story. In a recent TEDx talk, retired Atrium Health Chief Innovation Officer Dr. Jean Wright, also a member of the COPD Foundation board and one of the foremost thought leaders in the field, described COPD as an “invisible epidemic.” It turns out that even though we have successfully found those 15 million in the United States and 250 million around the world, it turns out that there may be twice that number walking around with symptoms, but without any clear idea why they can’t breathe very well, and therefore no treatment, education, or disease management plan. Dr. Wright calls these folks the “missing millions” of COPD, but whether they have a catchy label or not, it seems clear we must do a better job at identifying this population and getting them the care they deserve. In order to do that, we must first re-examine what we know about COPD, and then build a better system.

Why haven’t we found them? #

Historically, COPD has been closely associated with tobacco smoke, and even today (in the developed world) somewhere between 75-85% of cases are still linked to the use of tobacco products.3 This is logical, of course; cigarettes contain in the ballpark of 7,000 chemicals, many of which either directly damage respiratory tissues or weaken defenses against chronic infections, leading to more gradual damage. However, that still leaves a sizable portion of cases that have nothing to do with smoking. Ongoing exposure to atmospheric pollutants, chemicals, fumes, and dust in the workplace, and indoor air quality issues in the home can also lead to the same kinds of damage. In fact, in the developing world where people are more reliant upon traditional cooking and heating methods, exposure to smoke from biomass fuel sources is thought to be an even greater risk factor than cigarettes.4

There are a variety of other under-recognized risk factors for COPD. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is arguably the most well-known of these, comprising roughly 3% of all COPD cases. In Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, the liver creates malformed copies of the alpha-1 antitrypsin protein, which normally protects the lungs from irritants and infections. Without this protection, the lungs are much more susceptible to damage far earlier than normally seen in COPD. In addition, severe asthma that is suboptimally managed can eventually lead to airway remodeling and permanent obstruction. Certain severe infections can cause weakening of the airways with chronic bacterial colonization and ongoing infections, known as bronchiectasis. Even inflammation from conditions such as obesity and diabetes set the stage for obstructive lung problems later in life.

The misconception that COPD is always related to tobacco smoke is one of the greatest barriers to appropriately diagnosing the missing millions. When other potential risk factors are not considered, it becomes very easy for patients to chalk up their gradually increasing breathing difficulties to simply getting older, or perhaps being out of shape. Certainly, these issues can add to progressive dyspnea, but unless the correct root cause can be determined, continued exposure to the irritants will worsen the damage until it cannot be ignored anymore. Similarly, overworked clinicians in the primary care world, still operating under the assumption that one must be a long-term smoker to be at risk for COPD, simply don’t have time to be chasing ‘zebra’ diagnoses and often instead go with more obvious or immediate concerns. In other cases, primary care providers may not have the equipment necessary to make a proper COPD diagnosis available on-site. Historically, pulmonary function tests (PFTs) have been the realm of specialized facilities with cumbersome, technically complex, and delicate equipment. Many patients may be reluctant to add another stop to their healthcare ‘tour,’ once again delaying diagnosis and allowing damage to mount.

Unfortunately, it’s not just the lungs that bear the brunt of this damage, either. With oxygen being the primary fuel for cellular metabolism and carbon dioxide being the main waste product, seeing either of those fall outside normal ranges can wreak havoc on any organ system. Many who live with COPD (diagnosed or not) also endure cardiovascular problems; after all, the heart and lungs are essentially co-located in the thorax and like any neighbors, what affects one invariably affects the other.

The end of the tunnel #

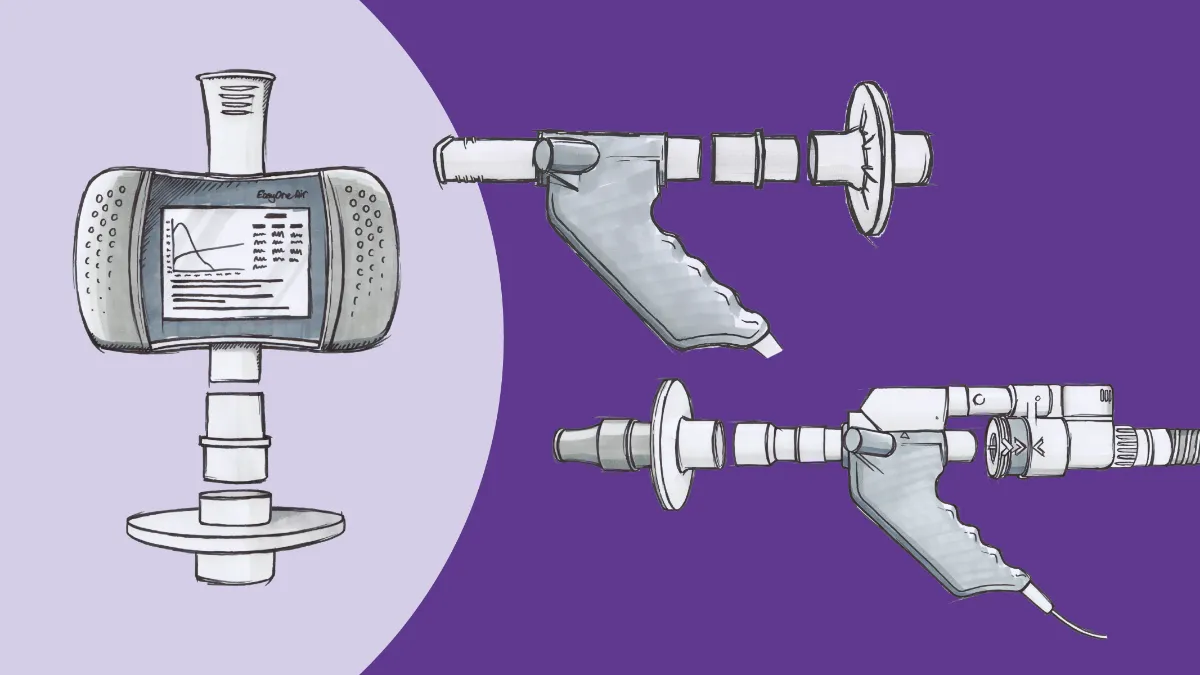

Note that it is only “historically” that PFT equipment has been hard to access. Fortunately, those days are now well behind us. The EasyOne Pro line of pulmonary function testing equipment from ndd brings the power of a full-featured PFT lab into virtually any setting. Both the Pro and Pro LAB provide access to the two most important testing modes (spirometry and diffusion capacity), as well as lung volume measurements, right at the point of care. Spirometry is long established as the definitive standard for COPD diagnosis, with groups ranging from the COPD Foundation to the American Thoracic Society to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) all using it as the basis for their diagnostic criteria. Modern spirometers are able to provide accurate flow and volume measurements (as well as preliminary interpretations of those measurements) quickly and easily, and ndd’s EasyOne Air device is rugged and portable enough to be used even outside the clinic. Spirometry values have the potential to detect airflow problems even before people experience symptoms, enabling the early diagnosis and management that can be essential for exposure mitigation and even potentially slowing disease progression.

The value of DLCO #

However, spirometry is not always enough. Surprisingly, not everyone with spirometric obstruction goes on to develop COPD symptoms, and conversely not everyone with debilitating symptoms has measurable airflow problems. That’s where that second mode, diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO) comes in. This test uses trace amounts of carbon monoxide gas to evaluate the gas transfer between the alveoli and the pulmonary vasculature. A recent paper using data from the landmark COPDGene population study concluded that reduced DLCO measurements are closely linked with the severity of COPD symptoms, as well as being predictive of outcomes in the disease.5 The ability to measure DLCO as part of a standard primary care exam provides a gateway to both faster diagnosis of COPD and more effective management of symptoms over the long term.

A cost-effective, patient-centric PFT solution #

With all those missing millions of COPD patients, not to mention all those living with interstitial lung diseases, cardiovascular problems, and the cornucopia of other conditions that affect breathing (not to mention the looming specter of long COVID cases), the need for widespread access to easy-to-use pulmonary function testing equipment has never been higher. PFT labs are still recovering from the service disruptions created by the pandemic, and it falls to other offices to provide innovative solutions to facilitate testing, diagnosis, and enhanced care.

Guarascio AJ, Ray SM, Finch CK, Self TH. The clinical and economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the USA. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:235-245. doi:10.2147/CEOR.S34321 ↩︎

Abbafati C, Machado DB, Cislaghi B, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204-1222. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 ↩︎

Jindal SK. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers - Is it a different phenotype? Indian J Med Res. 2018;147(April):337-340. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_10_18 ↩︎

Sana A, Somda SMA, Meda N, Bouland C. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with biomass fuel use in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2018;5(1):e000246. doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2017-000246 ↩︎

Balasubramanian A, MacIntyre NR, Henderson RJ, et al. Diffusing Capacity of Carbon Monoxide in Assessment of COPD. Chest. 2019;156(6):1111-1119. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.035 Balasubramanian A, Kolb TM, Damico RL, Hassoun PM, McCormack MC, Mathai SC. Diffusing Capacity Is an Independent Predictor of Outcomes in Pulmonary Hypertension Associat ↩︎