COPD awareness month: A call to action for primary care

The crisis of COPD underdiagnosis #

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death worldwide, leading to almost 4 million deaths in 2023.1 While highly prevalent, COPD is, perhaps surprisingly, underdiagnosed. Late diagnoses are the norm: Potentially around 2/3rds of all diagnoses are considered potentially late diagnoses2, given after the disease is considered more advanced. Late diagnoses are associated with worse outcomes, including higher rates of hospitalizations and healthcare utilization.234

Not only are a large subset of COPD patients diagnosed late and long after symptom onset, many millions of people are still living with symptomatic, undiagnosed COPD without even realizing it.

November is COPD Awareness Month, so this year, we are highlighting primary care clinics and the role they play in treating the population of people with COPD.

Primary care clinics, where most people with undiagnosed COPD are seen, offer a compelling opportunity to reduce the population of undiagnosed, symptomatic patients who would benefit from getting on the right treatment.

The role of primary care in COPD #

COPD is widespread and treatable, but people can’t receive the right treatment if they don’t know they have it.

COPD requires spirometry to confirm a diagnosis, which at present, is not currently feasible for most people since pulmonary function testing is not commonly performed at many primary care clinics. Primary care clinicians may or may not even be aware that some of their patients are experiencing respiratory symptoms.4

COPD-related symptoms can begin slowly and barely perceptibly. People with undiagnosed COPD may compensate for these early symptoms by reducing the amount of physical activity without even realizing they’re doing it.4 Early COPD symptoms can resemble aging-related symptoms, poor conditioning, or “smoker’s cough”, so patients may dismiss these symptoms and never report them to their primary care doctors.4

To address the crisis of undiagnosed COPD, GOLD, the Global Institute for Obstructive Lung Disease — a joint effort between the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (an institute in the National Institutes of Health) and the World Health Organization (WHO) — recommends targeted case finding and evaluation for COPD in people that present with risk factors or chronic respiratory symptoms.

Primary care clinics are well-positioned to implement GOLD’s recommendation. They are entrenched in their communities and see a wide range of people of all ages and conditions. They’re the first doctors to see people before they receive diagnoses for COPD, asthma, obesity, heart disease, and diabetes. With an increase in targeted screening practices, primary care doctors can reduce how many people continue to live with undiagnosed COPD.4

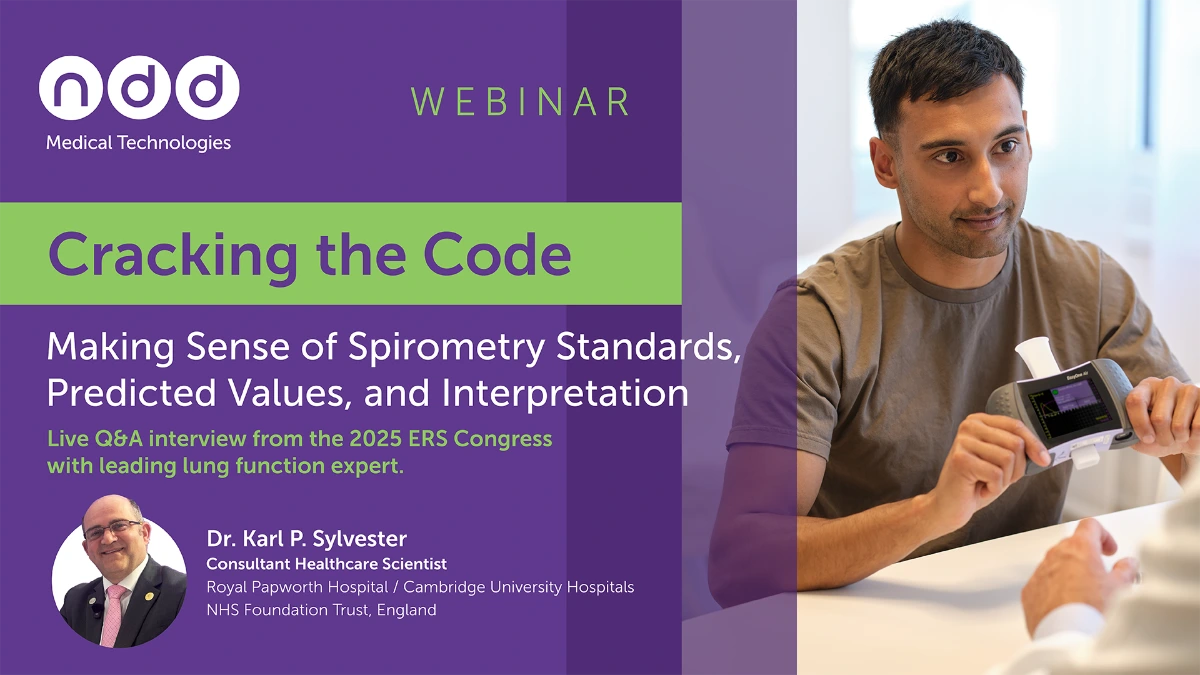

Why spirometry matters #

Historically, COPD was a diagnosis based on clinical assessment and personal history. Now, spirometry must be used to confirm a diagnosis of COPD.5

Without confirming COPD with spirometry, clinicians run the risk of misdiagnosing and overtreating somebody who may not have COPD.

Up to 62% of diagnoses made without spirometry are classified as misdiagnoses.6

Increased usage of spirometry in patients with COPD symptoms and risk factors can enable earlier detection. Earlier detection could also potentially reduce exacerbation rates and improve long-term patient outcomes through more timely initiation of therapeutic interventions, pulmonary referrals, and smoking cessation programs.

Barriers to spirometry in primary care #

For their part, primary care doctors may be less likely to test people for COPD since they either aren’t aware of their patients experiencing increased symptoms or due to not having a spirometer easily accessible to confirm a suspected case of COPD.

There are a lot of barriers to implementing spirometry in primary care clinics. There are concerns about staff expertise, whether implementing spirometry is too complicated for the clinic’s workflow, and whether it takes too long for clinic staff members to perform PFT testing.

Tips for integrating spirometry into primary care #

Fortunately, these barriers can be overcome using a few tips below.

Streamline workflows and effective technology #

Personnel bandwidth and previous experience do not have to prevent a clinic from integrating spirometry. There are courses available now that show that clinic staff can be trained to implement spirometry effectively and accurately.7

Modern portable PFT and spirometry devices, including EasyOne devices, have been validated in primary care clinics.89 EasyOne devices are also highly reliable and don’t require calibration.8 EasyOne devices are easy to use for patients and operators, requiring minimal training to ensure acceptable and reproducible tests.

Software concerns aren’t prohibitive either: integration with electronic medical records systems (EMR) can be seamless, reducing documentation burden and improving testing adoption.

EasyOne spirometry machines - tailored solutions for every practice.

Explore our spirometry machines

Make spirometry routine #

Screening at-risk patients is crucial for reducing the amount of undiagnosed people with COPD. But spirometry and screening must be routine to diagnose these individuals.

Diagnostic rates may be improved by including screening for COPD by first inquiring about respiratory symptoms and administering spirometry to those that qualify alongside other routine medical screening.

Educate and empower patients #

Patients must feel supported, listened to, and understood. Otherwise, they may not feel comfortable sharing their recent symptoms. Through trust and supportive relationship-building, primary care clinicians and patients can work together to identify when things are changing and patients are developing symptoms. When COPD and spirometry are explained in plain language, engaging, and accessible way, patients will feel more comfortable discussing symptoms and performing pulmonary function tests.

Conclusion #

COPD is a highly prevalent chronic condition that remains significantly underdiagnosed, in part due to lack of accessibility to spirometry. Due to primary care clinics being so deeply entrenched in communities with broad populations of people, these clinics are well-positioned to lead the charge in addressing the crisis of underdiagnosis in the COPD community.

Through streamlining workflows, implementing targeted screening campaigns with the use of symptom assessment and spirometry, and developing strong relationships with patients and explaining COPD and spirometry, primary care clinics can overcome the barriers commonly faced when implementing spirometry.

Naghavi M, Kyu HH, A B, et al. Global burden of 292 causes of death in 204 countries and territories and 660 subnational locations, 1990–2023: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. The Lancet. 2025;406(10513):1811-1872. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01917-8 ↩︎

Kostikas K, Price D, Gutzwiller FS, et al. Clinical Impact and Healthcare Resource Utilization Associated with Early versus Late COPD Diagnosis in Patients from UK CPRD Database. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:1729-1738. doi:10.2147/COPD.S255414 ↩︎ ↩︎

Soriano JB, Zielinski J, Price D. Screening for and early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet Lond Engl. 2009;374(9691):721-732. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61290-3 ↩︎

Yawn BP, Martinez FJ. POINT: Can Screening for COPD Improve Outcomes? Yes. Chest. 2020;157(1):7-9. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2019.05.034 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Agustí A, Sisó-Almirall A, Roman M, Vogelmeier CF, members of the Scientific Committee of GOLD (Appendix). Gold 2023: Highlights for primary care. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2023;33(1):28. doi:10.1038/s41533-023-00349-4 ↩︎

Jørgensen IF, Brunak S. Time-ordered comorbidity correlations identify patients at risk of mis- and overdiagnosis. Npj Digit Med. 2021;4(1):12. doi:10.1038/s41746-021-00382-y ↩︎

Coates AL, Tamari IE, Graham BL. Role of spirometry in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(12):1069-1070. ↩︎

Skloot GS, Edwards NT, Enright PL. Four-year calibration stability of the EasyOne portable spirometer. Respir Care. 2010;55(7):873-877. ↩︎ ↩︎

Hegewald MJ, Gallo HM, Wilson EL. Accuracy and Quality of Spirometry in Primary Care Offices. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(12):2119-2124. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201605-418OC ↩︎

Written by

Tré LaRosa

Tré LaRosa is a consultant, scientist, and writer in the Washington, DC area with extensive experience working in research (basic, translational, and clinical) and on patient-reported outcomes. He has also written extensively on neuroscience, pulmonology, and respiratory conditions, including from the patient perspective. He enjoys learning, reading, writing, spending time outdoors, and telling everybody about his mini golden retriever, Duncan.