The history of PFT - part 1

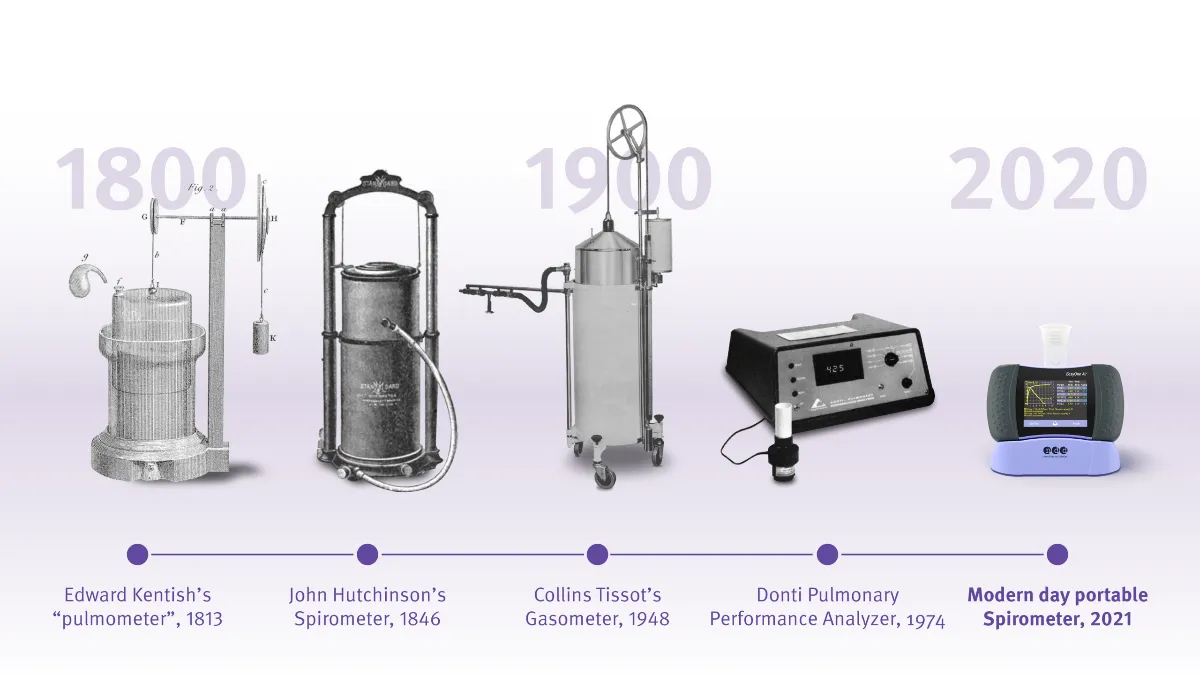

It’s easy to take pulmonary function testing for granted these days. After all, technology has literally put spirometry in the palm of your hand, and even equipment for more complex testing like diffusion capacity can now be made easily portable. But in order to really understand how remarkable these accomplishments are, it’s important to understand where it all began. This is Part 1 of our ongoing series on the history of pulmonary function testing.

The capacity of life #

In 1839, an engineer-physician by the name of John Hutchinson had an idea. He had recently been hired by the Britannic Assurance Society, a new firm jumping into the nascent London life insurance market.1 Up to that point, most life insurance was based on actuarial tables that were established from somewhat subjective things like alcohol consumption or malnutrition based on height and weight.

In Hutchinson’s view, the biggest problem with this data was it was based on questionnaires and thus were dependent upon people not hiding a suboptimal family history or otherwise obfuscating their risk. With Britannic Assurance being a new firm, they couldn’t afford to take on too much risk and chance pushing the company into financial ruin. They needed an objective way to figure out what someone’s lifespan was most likely going to be.

Spirometer precursors #

Hutchinson had seen several different designs for various types of apparatus during his time in medicine. There was the pneumatic trough, most often used to collect gases for the study of plant life2. There was the gasometer, the tool developed by no less a visionary than Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier for accurate measurements during the refinement of his oxygen theory. And there was Edward Kentish’s ‘pulmometer,’ which first gave the inklings that lung capacity may be related to disease processes.3

The various aspects and applications of these gadgets should allow for a more rigorous, scientific evaluation of lung status (and therefore life expectancy), at least to Hutchinson’s mind. So, the physician/engineer set to work refining the equipment, gathering in the various aspects of both storage and measurement devices, to create his own device. By 1844, Hutchinson had developed a device he dubbed the spirometer, combining the Latin words for “breath” and “measure,” presenting it (as well as data from it) at meetings of the Statistical Society of London and the city’s Society of Arts.

The Hutchinson spirometer #

Other than its size, the Hutchinson spirometer would probably not be completely out of place in PFT labs today. The basic design of the device is not dissimilar from a water-seal spirometer, thanks to the influence of its pneumatic trough predecessor. A person would exhale through a tube, displacing a certain amount of water and moving an indicator, which represented the volume of exhalation in cubic inches. The machine was also capable of being adjusted for atmospheric conditions with a series of pulleys and counterweights to allow the pressure inside the machine to match the ambient barometric pressure. It even included a thermometer for appropriate corrections.

However, it did have what we now know to be a major shortcoming; it could only measure volume, not flow. In theory, the flow could be measured with an appropriate timer or watch, but at this point, pulmonary testing was still new enough that this was not even known to be a concern. Volume was everything.

Early pulmonary function testing #

While these were not complete PFT machines as we know them today, they were certainly not crude or unsophisticated either. Hutchinson was able to work with some of the finest instrument makers in all of London, allowing the initial device to be constructed within exacting tolerances. He was also able to work with professional groups of the time to recruit operators for his machines, creating the forerunners of today’s pulmonary function technologists.

As a science professional, Hutchinson also knew the importance of standardized testing regimens, and the set he developed for use with his new device included detailed instructions on how and in what order to perform tests in order to optimize data quality, once again much like modern PFT lab protocols. Having a solid set of procedures, a high-precision machine, and skilled technicians enabled Hutchinson to compile some of the first epidemiological datasets available on lung function, as well as determine factors that affect one’s vital capacity.

Foundational concepts of pulmonary function testing #

Hutchinson and his team collected data from thousands of Londoners in varying degrees of health and from assorted walks of life. Remarkably, using these now-rudimentary machines revealed many of the foundational concepts of pulmonary function still accepted today. Hutchinson’s work confirmed that vital capacity was directly related to certain physical factors, such as height and abdominal mass. He demonstrated that age could have an impact on function, trending his own vital capacity over the course of several years.

At one point, he demonstrated to an auditorium of physicians and scientists that he could accurately predict their vital capacity based on their age and height alone. Data was also compiled for various occupations, allowing for preliminary comparisons based on physical conditioning and similar factors. Unfortunately, women were largely excluded from the evaluation (and therefore the development of predictive charts), not due to any scientific reason but because the modesty standards of the time generally prevented them from removing enough clothes for the same kinds of chest measurements and other evaluation that allowed for the creation of datasets for men. This issue persisted long after Hutchinson’s era and highlighted how controversial “normal values” can be.4

To his credit, however, Hutchinson was also eventually able to attribute differences in vital capacity to the tightness of clothing, allowing for a better understanding of those physiological differences between the sexes, rather than simply assuming women just breathed differently than men.

Early spirometry in the diagnosis of respiratory diseases #

Despite that gap, the data also allowed for predictions based on disease state. Tuberculosis (TB) was the prevailing respiratory concern of the time, particularly when it came to Hutchinson’s twin responsibilities as a medical advisor to a life insurance provider and a practicing physician in a hospital specializing in TB. In an era without chest X-rays (even before medicine knew what was even causing the dreaded ‘consumption’), testing for vital capacity was found to a dependable tool for diagnosing TB presence and severity. A change in the vital capacity of as little as 16% below the predicted value appeared to distinguish people with TB from their healthier counterparts, leading some to assert that spirometry was superior to the other diagnostic tool in wide use (auscultation) for diagnostics, even though the stethoscope had been in use for three decades by then.5

Hutchinson’s later life and career #

Hutchinson spent the remainder of the 1840s continuing to collect vital capacity data, publish his findings, and enhance the body of knowledge of pulmonology. In addition, he continued to refine the design of the spirometer, making it more compact and practical for use in a variety of settings. However, by 1852, he had apparently grown somewhat bored with life in London, packed up his belongings, and moved to literally the other side of the world, settling in Australia.

Little is known about why Hutchinson moved or his time there, other than it took him several years to re-establish himself as a physician. Some believe he moved there hoping to find fortune in the Australian Gold Rush, while more salacious stories about domestic strife also abound. In any event, he appears to have left his interest in spirometry and epidemiology both back in his London office, as he never wrote on either subject again. In early 1861, he moved once again, this time to the island of Fiji, where he unfortunately contracted dysentery after arriving. John Hutchinson died later that year, leaving behind a vital legacy that continues to influence pulmonary function devices to this day.

Continue reading - The history of PFT - part 2

Speizer FE. John Hutchinson, 1811–1861. Epidemiology. 2011;22(3):e1-e9. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e318209dedc ↩︎

The Origins of the Spirometer | PFT History. https://www.pftforum.com/history/gallery/the-origins-of-the-spirometer/. Accessed November 12, 2020. ↩︎

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier The Chemical Revolution - Landmark - American Chemical Society. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/lavoisier.html. Accessed November 12, 2020. ↩︎

McGuire C. The spirometer and the normal subjects. In: Measuring Difference, Numbering Normal. ; 2020. https://www.manchesteropenhive.com/view/9781526143167/9781526143167.00013.xml. Accessed November 12, 2020. ↩︎

Gibson G. Spirometry: then and now. Breathe. 2005;1(3):207-215. https://breathe.ersjournals.com/content/breathe/1/3/206.full.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2020. ↩︎